EMMA LYNCH/BBC

EMMA LYNCH/BBC

Dozens of rivers and canals were buried beneath London's streets more than a century ago. How do they look today? To find traces of them you'll need to have a good ear, know where to look and visit some unlikely places.

Among the congested traffic of central London's St Pancras Road, around the corner from the glass and steel skyscrapers of the Euston Road, it is hard to imagine a river once ran through grassy fields.

But outside St Pancras Old Church is a plaque showing a sketch of people in that exact spot bathing on the banks of the Fleet in 1827. The river is one of many in London that was converted into a sewer as the capital's population grew.

Today, in many parts of the city you could be standing within inches of one of its lost rivers and not even realise it.

"Wherever you live, not far from your doorstep, you can probably track down a hidden river you never would have guessed would be there," says Alex Werner, head of history collections at the Museum of London.

"It's a shame so many rivers were buried - today they would enhance the landscape," says Paul Talling, who has written a book on London's lost rivers. "But at the time it was necessary - in pre-Victorian times, they were used as open sewers."

PAUL TALLING

PAUL TALLING EMMA LYNCH/BBC

EMMA LYNCH/BBC

The Fleet is probably one of the better known rivers that lies beneath Londoners' feet.

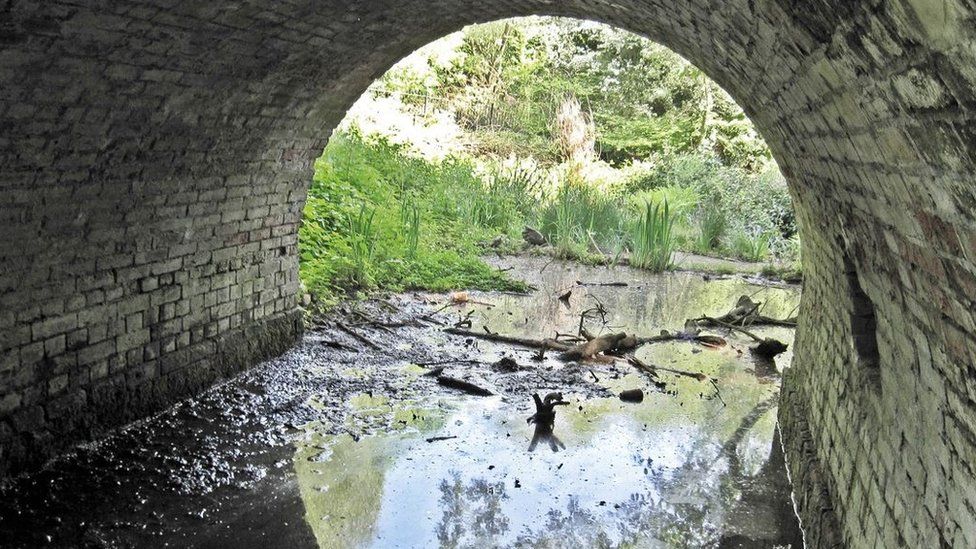

Vestiges of it can be traced above ground by following a modest stream that flows from Hampstead and Highgate Ponds, in north London.

But these days it is swiftly submerged, becoming a sewer that flows to Blackfriars Bridge on the River Thames.

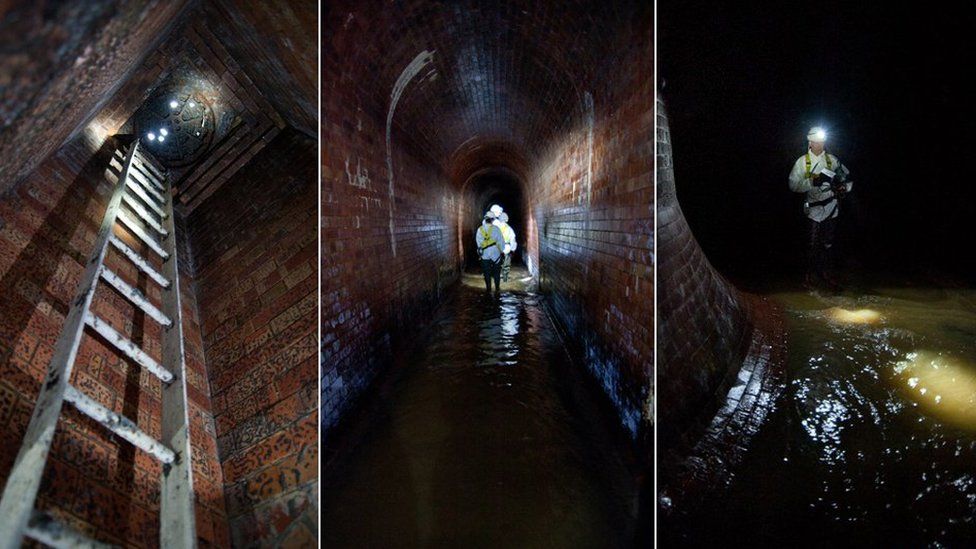

When I visited, dressed in stylish white overalls and waders, via a manhole on Farringdon Road, unsurprisingly, what struck me first was the smell.

Once you get over that, you began to appreciate the 150 year-old Victorian brickwork remains in a surprisingly preserved state.

"The atmospheric conditions are pretty constant so you don't need to do much maintenance on the brickwork," says Thames Water's field operations manager Daniel Brackley.

Heavy, rusty rings line the tunnel walls. "It's purely speculation but some people say the rings are from when people tied up barges against the river bank," he says.

London's rivers have been through massive transformation over the centuries.

"Back in the early days they were used for drinking and fishing," says Mr Talling. "The springs fed wells such as Clerkenwell, where the clerks of the parish would drink water."

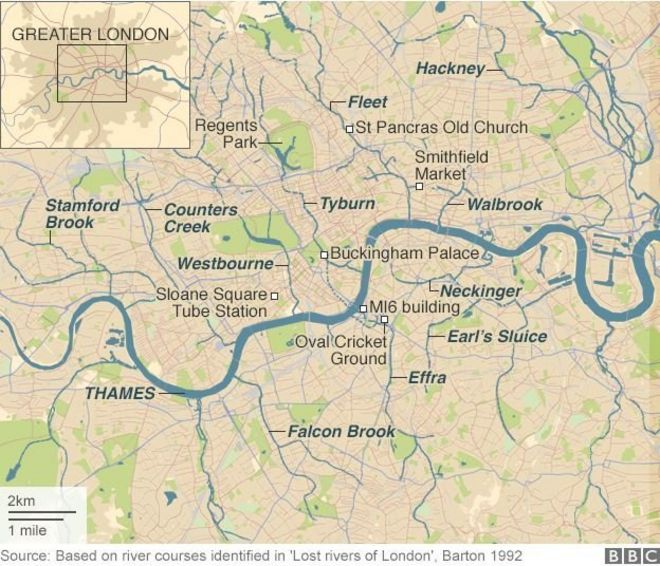

London's lost rivers

PAUL TALLING

PAUL TALLING

River Fleet - Became polluted as Smithfield butchers threw remains of dead animals into the river, and was eventually incorporated into the sewer system

River Tyburn - Flowing through Regents Park under Buckingham Palace, the river was once reputed to have some of London's best salmon fishing

River Walbrook - Its name is thought to derive from the fact the river ran under the Roman London Wall

River Westbourne - Remains of the river flow through a pipe running above Sloane Square Tube station

River Effra - Banks of the Oval cricket ground were built with earth excavated during the enclosing of the river

The Fleet was once a broad tidal basin, several hundred feet wide when it reached the Thames, but like many of London's other rivers, its flow greatly reduced as the city's population grew and it became an open sewer.

"The area became unpleasant and the land became cheap," Mr Talling says.

In fact, the Fleet's reputation for slum dwellings, crime and disease was such that Charles Dickens based Fagin's Den in Oliver Twist in the area it flowed through.

Following the Great Fire of London in 1666, the capital's rivers became integral to Christopher Wren's redevelopment plans for the city.

"The vision was to have canals with arch bridges like Venice," Mr Talling says. "But in reality, the sewage meant it just got clogged up."

PAUL TALLING

PAUL TALLING

Sections began to be covered and, following the Great Stink of 1858, were incorporated Joseph Bazalgette's designs for the sewer system that remains today.

The rivers may now be subterranean but their impact on London's landscape remains.

"You can see the shape created by the Fleet Valley on the Farringdon Road," says Mr Talling, who organises walking tours along some of the lost rivers' paths.

Meanwhile, borders between different parts of the capital owe much to its buried waterways.

"If you follow the course of the River Westbourne, one side of the road is Kensington & Chelsea, the other side is Westminster," Mr Talling says. "It's quite confusing for people parking cars."

EMMA LYNCH/BBC

EMMA LYNCH/BBC WALBROOKDISCOVERY.WORDPRESS.COM

WALBROOKDISCOVERY.WORDPRESS.COM

The damming of the Westbourne was ordered by George II's wife Queen Caroline in 1730 to form the Serpentine and increase Hyde Park's aesthetic appeal.

"The Serpentine was expanded in the 18th Century to make the park look more beautiful," Mr Werner says.

"But the water from the Westbourne became too polluted, so in the end they had to pipe it under the park," says Mr Talling.

"Now the Serpentine is sourced by water from a pumping station by Chelsea Bridge and the ornamental waters in Kensington Gardens."

Elsewhere, in south London, the raised banks of the Oval cricket ground were built with earth excavated during the enclosing of the Effra.

"The river showed itself again and was responsible for flooding the cricket ground in the 1950s," says Mr Talling. "The rainfall became excessive and the torrent of the flood meant the sewers overflowed."

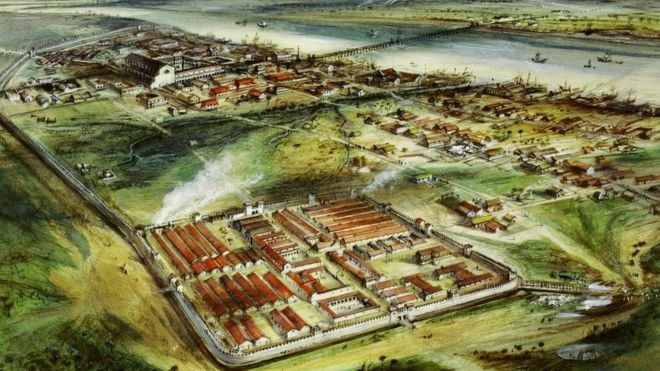

Back over the Thames, in central London, the River Walbrook dates back to Roman Londinium, with John Stow's 1598 Survey of London suggesting its name derives from the fact the brook passed by the city wall.

On a Saturday afternoon in September 1954, along the path of the river, what is widely regarded as the City of London's most famous Roman discovery of the 20th Century was made.

Welsh archaeologist Prof WF Grimes discovered a Roman temple devoted to god of light Mithras.

The discovery of the temple was in Grimes' own words "a fluke".

ALAN SORRELL/MUSEUM OF LONDON

ALAN SORRELL/MUSEUM OF LONDON

"Professor WF Grimes wasn't looking for a temple but rather wanted to learn about the Walbrook Valley and its stream," says Caroline McDonald, the Museum of London's senior curator of Roman history.

Now, after centuries of burying London's rivers, there is a campaign to restore one of them above ground.

The Tyburn Angling Society has gained publicity in recent years for its proposal to restore the River Tyburn - which originates in Hampstead, before flowing through Regent's Park then into the Thames at Pimlico - as a prime fishing stream.

The plans are ambitious to say the least. To come to full fruition, they would require destruction of billions of pounds worth of property including Buckingham Palace.

But the group's spokesman James Bowdidge still thinks it may one day happen.

"The proposal is very realistic, sustainability at its purest," he says. "With the support of the public and of landowners, we will bring wildlife, fishing and beauty into the heart of Mayfair."

So who knows, one day, when heading to the West End, you may well want to pack your waders and fishing rod.

EMMA LYNCH/BBC

EMMA LYNCH/BBC